Previously we discussed some of the core tenets of the incoming Trump administration’s economic plans. We’ve covered his plans to apply universal tariffs against allies and enemies alike, mass deportations, and tax cuts. While the tax cuts could be beneficial if constructed correctly, it’s difficult to see upside for the tariffs and deportations. His tariff plan will likely be met with retaliatory tariffs from trade partners, which could damage U.S. growth, along with the rest of the world. If deportations are large and undertaken quickly, it could trigger a labor shortage in industries such as agriculture and construction, which would be inflationary.

The fourth major pillar of the Trump economic plan applies to energy. More specifically, Trump is looking to increase U.S. production of crude oil by opening government land where drilling had been banned, and by relaxing environmental regulations. Increasing supply will lower the price of crude oil, which will in turn lower gasoline prices, allowing for American’s incomes to stretch farther, and raising standards of living. At least, that’s the premise. It all sounds wonderful, simple, and straightforward. Yet, energy markets are anything but simple. The major irony here is that we likely don’t need to expand areas for drilling in the U.S. to bring oil prices down. Production in the U.S. has been steadily increasing for almost 20 years, and the Energy Information Administration (EIA) is predicting a global supply glut for the next 2 years.

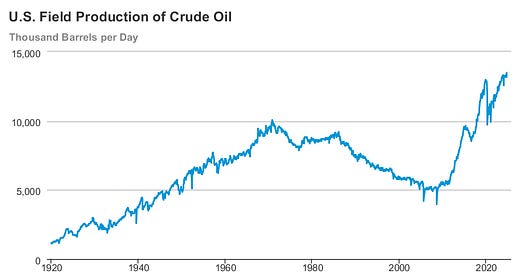

Below in Chart 1, we can see U.S. production of crude oil going back to the 1920s. Some interesting trends can be seen. Crude oil production rose steadily from when oil was first discovered until around 1970. U.S. production started to decline in the early 1970s as the reality of “Hubbert’s Peak” began to take hold. Geologist M. King Hubbert developed a theoretical model to measure the growth and decline of oil production in a certain geographical area. The 70’s were a particularly turbulent time in part due to this drop in U.S. production, as Arab countries acquired excess clout in oil markets, and utilized it to punish the U.S. through embargos for supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

Chart 1

The mid-2000s were a watershed period for U.S. oil production, as new technology, “fracking”, changed the oil production game drastically. Oil fracking, short for hydraulic fracturing, is a method used to extract oil and natural gas from underground rock formations, particularly shale. The process involves injecting a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and chemicals into the rock, creating fractures that allow oil or gas to flow more freely to a well. This technique has significantly boosted oil and gas production, particularly in the United States, contributing to energy independence and lower energy prices.

Covid Crude Glut

Once again, Chart 1 shows an extraordinarily sharp trend higher in oil production starting in the mid-2000s that persisted throughout the Obama and Trump administrations. The major hiccup came during Covid lockdowns, when global economic activity dropped precipitously. Oil production collapsed as a massive glut formed, and storage capacity was maxed out. Chart 2 shows an interesting illustration of how severe the glut was. Crude oil futures at one point plunged to negative $40, as oil buyers had no way to take delivery due to lack of storage capacity! This was the first time in history that oil futures traded at negative prices.

Chart 2: Crude Oil Front Month Futures

The drop below $0 for crude oil futures is not just historical trivia – it illustrates an important concept. Producers must believe they can sell oil at a profitable level, or they will cut production. When this price shock hit the system, oil production cratered. It’s not rocket science, but bears mentioning because it’s a major caveat. Too much production can cause prices to fall below where certain producers have the ability to profit.

As mentioned before, crude oil is a global market, which means that there are producers around the world. The dominant player in the global market since the 1970s has been the OPEC cartel, with Saudi Arabia as the largest producer. Saudi Arabia has been the leading global producer for most of the last 40 years, but the extraordinary growth of U.S. production in the last 20 years has now placed the U.S. as the biggest producer.

Most OPEC countries are dependent on oil revenue to balance government budgets, which has been their primary reason for restricting supply through the years to maximize oil revenue. For the last several decades, whenever oil prices slipped below levels thought to optimize revenue, OPEC countries sought to cut production. The rise of U.S. production may have changed that. Most experts believe OPEC may no longer be able to control prices in the oil market. Repercussions of this have yet to be felt in the U.S. That is, gasoline prices, while lower than they have been in a while, are still elevated by historical standards.

Gasoline Prices Are Not Elevated by Lack of Crude Supply

Chart 3 shows the price of crude oil with gasoline prices from the early 1990s to now. Not surprisingly, the two tend to move in lockstep, but in the last 10 years the gasoline price has been more elevated relative to crude prices. With crude at its present price, gasoline would have likely averaged 10-15% lower in previous years. There are various reasons for this change. First of all, the Russia war with Ukraine has affected energy markets negatively as sanctions have been applied, but gasoline prices can be elevated relative to crude oil prices due to several other factors, including refining capacity constraints, seasonal demand fluctuations, and regional supply disruptions. When refinery capacity is limited, especially during maintenance periods or unplanned outages, the supply of gasoline can be restricted even if crude oil supply remains steady.

Chart 3: Crude Oil Prices (blue) vs. Gasoline Prices (orange)

Crude oil markets are global markets, with the product considered to be mostly fungible. There are different grades of crude oil, but for the most part they are interchangeable. Differences in the grades involve the level of sulfur and viscosity, which requires variable refinery designs and construction, but this washes out on a global basis. However, due to the history of the global oil industry, this can create bottlenecks in certain countries. In the U.S. for instance, most of our refinery capacity is designed to take in the sort of heavy sour crude produced by Saudi Arabia, because for decades that was most of the oil to which we have had access.

Since the “Shale Revolution” took hold, that mix has changed. U.S. shale oil is much “lighter and sweeter” than the oil we buy from Saudi Arabia, which means we have an excess of light sweet crude and must still import Saudi Arabian oil to optimally utilize our refinery capacity. What isn’t used here gets exported. The U.S. now exports around 4 million barrels per day.

The upshot is that the “Drill Baby Drill” policy is not the game changer some believe it to be. First, if U.S. crude oil production continues to grow at the present rate, in a couple of years the U.S. will be producing triple the amount produced in the mid-2000s. Despite this extraordinary growth, gasoline prices have remained somewhat elevated in recent years. The EIA is projecting that the next two years will see a global crude oil surplus, and that crude oil and gasoline prices will likely fall. Assuming this doesn’t come about due to a global economic slowdown, it will be a nice tailwind for the U.S. consumer.

Reckless and Needless

Gasoline prices have been one of the major complaints of MAGA voters, which explains why it became a primary part of the Trump economic plan. Interestingly, the “Drill Baby Drill” slogan first materialized in the 2008 presidential campaign, when fracking was still in its infancy. At that time, it made a lot more sense. Proven global crude supplies seemed to be waning, “Peak Oil” was the largest theme in energy and equity markets, and the crude price had topped $160 by the middle of 2008, and the U.S. was only producing about 5 million barrels a day.

We’re in a completely different environment now. The crude price is less than half where it was at the 2008 top, and gasoline prices are not being held up by lack of crude supply. Presently, the U.S. is producing about 13.5 million barrels of crude a day. Renewables have made a lot of headway in terms of efficiency and are around 25% of electricity production now. NASA has recently confirmed that 2024 was the hottest year globally on record, and that record has been broken multiple years in a row.

There’s a reason the world has been working for years to reduce the use of fossil fuels. As experts have predicted, storms have been more extreme in recent years right along with the rising temperatures. Reversing environmental policies right now to attempt to bring down gasoline prices a marginal amount is profoundly reckless – particularly given that it seems to already be happening anyway. Sadly, this sort of political gamesmanship is par for the course these days, and it’s only going to get worse before it gets better.